Growing up, my concept of what people did while vacationing was influenced just as heavily as my concept of what made people “beautiful” or what brands made people look “cool”. The image I was sold was one of old buildings, breathtaking nature, locals dressed in traditional clothing, exotic animals, and mouthwatering cuisine. I was twelve when I went on my first vacation abroad, and my family checked every box on the list.

We took hundreds of photos of important-looking structures, visited stunning coastlines and countrysides, befriended a tortoise, posed with locals, and thoroughly embraced the regional palate. Afterwards, we flew home, imported our six hundred photos, only liked thirty of them, parroted the same summary of events to friends and family (who seemed more enamored with the fact that we left the country than what we actually did while abroad), then returned to our normal routines. That was the lifecycle of a vacation, and it would remain unchanged until 2018 when a friend from college invited me to her wedding in Spain.

She was marrying a Spaniard whom she had met while hiking Machu Picchu, and they were tying the knot in his home city of Sevilla. I was now twenty-eight and about to take my first international trip since my voice dropped. On the day of the wedding, I was struck by how international the groom’s friends were. Afterwards, I remember thinking, “Wow, I had the most interesting conversations last night. I need to make more international friends.” When I returned to the States and friends asked me how my trip was, I found myself raving about the fascinating people I met, not once mentioning the Plaza de España, the Alcázar, or the Catedral de Sevilla.

Four months later, I moved to Berlin. Similar to Spain, the major tourist spots took a back burner to meeting new people and integrating myself into my new home. I was far more enamoured with walking through the different neighborhoods and watching the ebb and flow of daily life than I was with visiting the glass dome of the Reichstag or going up the Fernsehturm.

By the time I left Berlin, the traditional vacation experience that I had been raised on ceased to exist. I barely took photos (and if I did, they were with friends), I actively avoided tourist attractions, and I could care less about finding the best “local spot” to eat. When the restraint of time was removed, I felt my conditioned desire to site see fade away and in its place grew a hunger for conversation and genuine human connection. I realized that a city isn’t defined by its monuments, but the people who walk its streets.

When I began facilitating trips for Hacker Paradise, this sentiment intensified. With each new city, I became more outgoing and opportunistic with how I made connections, prioritizing time with people above time at places. I didn’t always make local friends and it wasn’t always easy, but if you possess a genuine curiosity about the place you are in, people will open up to you, and knowing “hello”, “bye”, “please”, and “thank you” in the local language is a great first step.

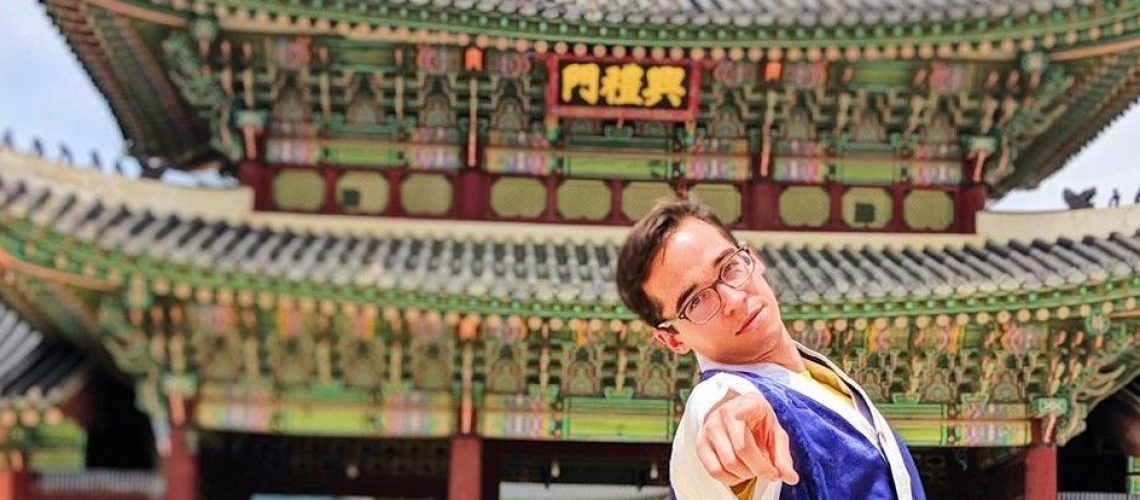

After five months of nomading, my fondest travel memories still consist entirely of moments that I’ve had with people: the bus ride to the suburbs of Budapest to eat watermelon and play Hungarian board games, eating dumplings in Gangnam and discussing whether young Koreans care about reunification, and dishing about dating and currency fluctuations while cooking Peruvian food in Buenos Aires.

I still consider myself a tourist in every city that I visit, but instead of filling my day hopping from attraction to attraction, or checking off a list of “must-try” restaurants, I like to take long walks with no real purpose other than to see how the denizens of the city live, what is different, what is similar, and maybe, if I’m lucky, I’ll find someone to talk to and ask him questions about his life. To me, that is the most authentic way to experience a city.

So, even though my departure from traditional tourism began before I became a nomad, being a professional traveler has affirmed my conviction that conversation is the best way to understand and experience the countries and cultures that I visit. And it’s made me realize that, for me, the end goal of traveling is not a curated Instagram feed to show off my worldliness, it’s a network of people from every corner of the globe with whom I’ve shared a slice of life. It is the grocer in Korea who helped me pick out the hot peppers using only hand gestures and the Swiss jazz musician in Budapest who needed help finding his car. These are the souvenirs of humanity that I will cherish more than any postcard.